The sea cucumber that lives like a jellyfish has been introduced. The Pelagothuria natatrix is a very uncommon species of sea cucumber that spends most of its life swimming and has a gelatinous body.

Not a Jellyfish

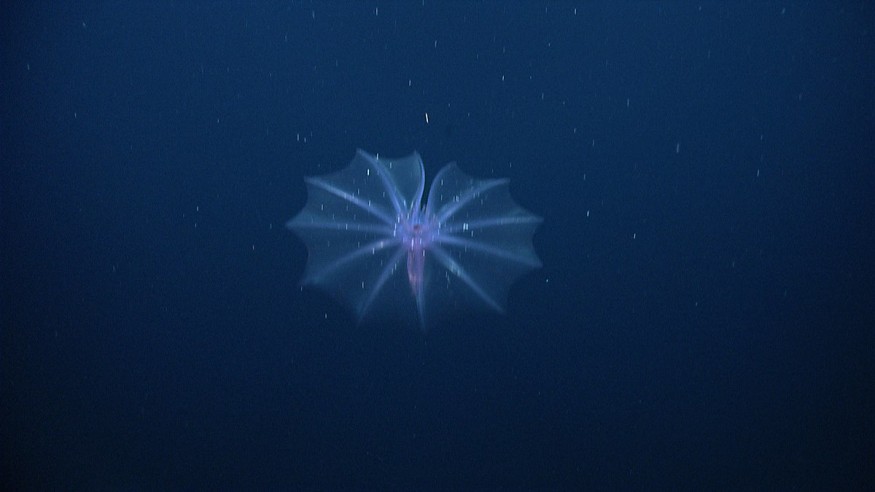

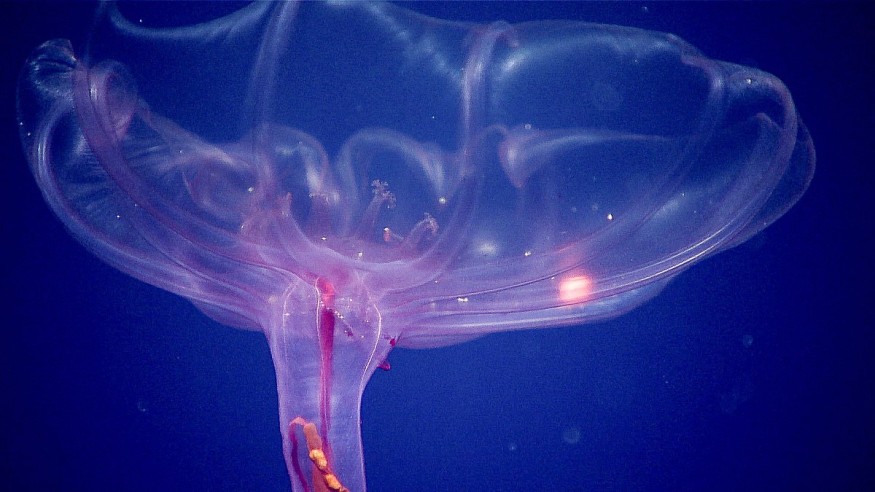

A diaphanous species, which looks like a jellyfish but is something entirely different, is wafting over the deep oceans. The name "swimming sea cucumber," Pelagothuria natatrix, refers to an animal more commonly recognized for lazing around on the ocean floor like enormous rubber worms.

Discovering the Deep-Sea Cucumber

The name of this sea cucumber dates back to the late 19th century, but for a very long time, all that was known about it came from a few beaten-up individuals caught in scientific trawl nets. According to Chris Mah, a biologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, "they're exceedingly delicate, almost to the point of being sort of intangible." They are pretty challenging to analyze since they are gelatinous.

After stumbling onto an umbrella-shaped Pelagothuria that had been mistaken for a jellyfish in a database of deep-sea photographs in 2014, Mah set what he terms a "rediscovery" of the species in motion. He claims that only a few scientists had ever heard of the species. Mah's discovery inspired others to keep an eye out for them when conducting deep-sea surveys.

Three years later, a group of scientists exploring the Pacific Ocean witnessed these delicate organisms in their native habitat with breathtaking clarity. The crew, who were based on the research vessel Okeanos Explorer, observed live video feeds of Pelagothuria that were transmitted by a deep-diving robot.

Finding a Hundred Cucumbers

They found around 100 of these swimming sea cucumbers during nine dives between American Samoa and Hawaii, frequently in regions with extremely low oxygen levels and depths ranging from 196 to 4,440 meters. Mah speculates that Pelagothuria may have adopted this strategy to evade predators that are more oxygen-hungry and more likely to suffocate.

A Unique Species

It is yet unknown how Pelagothuria manages to endure such trying circumstances, although it probably has something to do with its jelly body. A minor quantity of collagen is incorporated into the predominantly water-based bodies of many deep-sea organisms. Animals living at depths where food is frequently sparse would benefit greatly from the gelatinous goo's low energy requirements for production and maintenance. Animals made of jelly are also naturally buoyant, so they don't need to spend energy and oxygen moving frantically to remain afloat; instead, they can merely drift.

Pelagothuria is the only sea cucumber species known to spend most of its time swimming out of the estimated 1,200 species. It moves through the water column using the web surrounding its mouth.

Other varieties of sea cucumbers occasionally swim. They can swim when they want to, but they live on the bottom, according to Mah. A lethargic sea cucumber may become active in response to a predatory starfish's approach. It only takes a few awkward seconds of swimming to get away.

This might be how Pelagothuria's ancestors began, improving their swimming abilities until they accepted a full-time existence as jellyfish. It is an example of convergent evolution, whereby distantly related organisms-in this case, sea cucumbers and jellyfish-have encountered problems and come up with comparable solutions.

Swimming Jellies

In midwater species, you "certainly witness a lot of the gelatinous manner of existence," claims Mah. Every creature will have a different origin tale because it is a frequent adaptation.

Related Article : Sea Cucumbers Now the Face Of Aquacentric Organized Crimes

For more news about biology, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.