Photosynthetic organisms like Algae, Bacteria, and Plants use light as their number one source of energy. A fuel of some sort. However, too much light can be a bad thing.

Too much exposure to light can damage the photosynthetic lifeform's internal machinery, and that can lead to cell death and eventual degradation of the organism.

Like a car filled with too much fuel, a photosynthetic organism exposed to too much light energy is bound to burn. Literally.

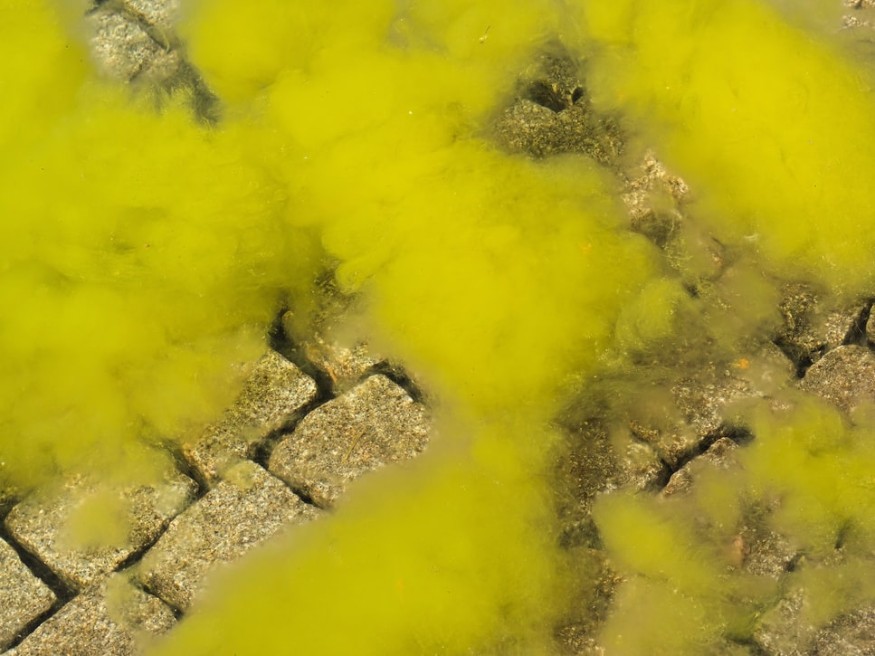

In a study published in Science Advances last January 6, 2021, a group of researchers from the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) revealed that the core structure of cyanobacteria, also known as the blue-green algae's light-harvesting antenna, includes an important feature that functions as an energy collector and a safety block for excess light absorption.

Photosynthetic Absorption

Photosynthetic light absorption is when photosynthetic organisms used the organs in their system to start absorbing certain light radiations as a form of food.

For algae and other higher plants, the photosynthetic pigments are located in the chloroplasts where the photosynthesis process takes place. The pigment molecules are not dispersed randomly within the chloroplast but are arrayed on the thylakoid membranes' surface.

The chloroplasts become oriented in such a way as to present a large surface area to the sun or other light source, thereby maximizing the pigments' ability to absorb light energy. In photosynthetic bacteria, the light-absorbing pigments are not organized in chloroplasts but are located on membranes dispersed throughout the cell.

ALSO READ : How can Plants see Blue Light?

The group of scientists from WUSTL created a large protein complex model called the phycobilisome used to collect and transmit light radiation and energy.

Phycobilisome allows the cyanobacteria to expose themselves to a wide variety of different light wavelengths that other photosynthetic organisms, i.e., plants, find harmful.

This ability greatly increases the global productivity from photosynthesis across the solar energy spectrum. However, it came with significant risk.

According to Haijun Liu, one of the research scientists in Chemistry from the Arts and Sciences department of the WUST, an excess of light absorption for the cyanobacteria is inevitable and potentially lethal.

They found an interesting structural feature when the energy was transferred and regulated. It showed that one of the regulation process, the non-photochemical quenching, is done by a protein known as the orange carotenoid protein.

A high-resolution structure of the phycobilisome will allow us to understand such processes in detail. While researchers already knew that orange carotenoid protein helps protect cyanobacteria during high light conditions, they did not picture all of the structural features at work.

The team also failed to determine where and how the orange carotenoid protein is sequenced in a living cyanobacteria's cellular structure.

They were stunned when they first found the current model. Liu's team immediately noticed that an inactive orange carotenoid protein could actually access or fit into the vacant spaces between the phycobilisome and PSII (the protein complex that receives energy from phycobilisome for photochemical reactions). Then it is ready to be recruited or activated by environmental cues.

This discovery is seen as a remarkable milestone for the future of energy absorption applications and research.

For more news about Cellular Technology, follow Nature World New

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.