After months, even years, of research and development, researchers from the University of Tokyo developed a new way to improve the scopes and limitations of former methods for cellular data gathering. It is able to show the insides of living cells using microscopy techniques without using the traditional staining or fluorescent dyeing.

Cells are naturally translucent, meaning; microscope cameras must be able to detect incredibly minute and subtle differences in the light that passes through the parts of them. Those smallest differences are the light's natural phase. Imaging and photo capturing devices like cameras, for example, have been under the limitation of what amount of light the difference in degree can detect. This is called the dynamic range.

As what the University of Tokyo'sTokyo's Institute for Photon Science and Technology Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi said, "To see greater detail using the same image sensor, we must expand the dynamic range so that we can detect smaller phase changes of light." And that is what the researchers did using the ADRIFT-QPI (adaptive dynamic range shift quantitative phase imaging).

"Our ADRIFT-QPI method needs no special laser, no special microscope or image sensors; we can use live cells, we don't need any stains or fluorescence, and there is very little chance of phototoxicity," said Ideguchi.

Phototoxicity is the method that involves killing cells that carry a significant amount of intense light, which can hinder imaging techniques like fluorescence imaging.

In a related article, Biology Filled Anime 'Cells At Work!' Gets Praise From Cancer Researcher

ADRIFT-QPI

Quantitative phase imaging sends pulses of flat sheet light towards the cell. Then, it measures the phase shift of the light waves while passing through the cell's structures. After that, the computer then analyzes and reconstructs the image of the structures inside the cell.

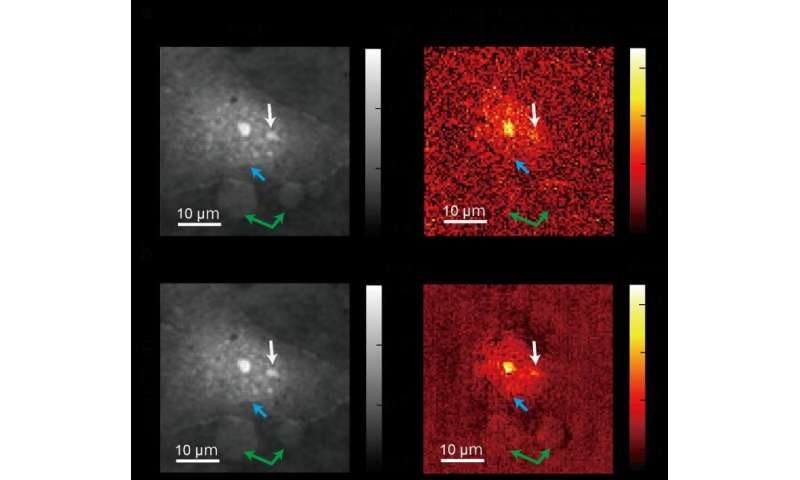

The new ADRIFT-QPI method has overcome the dynamic range limitation of quantitative phase imaging. During ADRIFT-QPI, the camera takes two exposures and produces a final image with seven times greater sensitivity than traditional quantitative phase microscopy images.

It is a powerful method for examining individual cells because it gives researchers the chance to make detailed measurements of the cell's specific activities without sacrificing quality over precision or precision over quality. A relatively better option compared to the traditional approaches.

As seen in the image above, the first exposure (top) shows imperfections, so the light waves emerged with phase deviations.

Meanwhile, on the second exposure (bottom), tiny light phase differences that were not found in the first exposure can be seen. This accuracy was the result of the greater sensitivity managed to show by the quantitative phase imaging.

Ideguchi says that the real benefit of ADRIFT-QPI is its ability to see tiny particles in the whole living cell context without needing any labels or stains.

"For example, small signals from nanoscale particles like viruses or particles moving around inside and outside a cell could be detected, which allows for simultaneous observation of their behavior and the cell's state," said Ideguchi.

Despite the exemplary achievement that Ideguchi and his team managed to reach, dozens of researchers and scientists still continue the search for improvement in the field of cellular microscopy.

For more news about Cellular Technology, follow Nature World News

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.