Conservationists have been struggling to determine how to effectively fight off invasive species in our international ports for some time, but now we may finally see notable improvement thanks to a computational analysis of the most at-risk regions. According to a new study, if we focus on a small number of key ports in particular, invasions can be handily managed.

The results of this study were presented by project leader Nitesh Chawla at the Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining in New York City just last month.

According to Chawla, he and his colleagues from the University of Notre Dame have designed software that can identify which ports are major hubs for the spread of aquatic invaders.

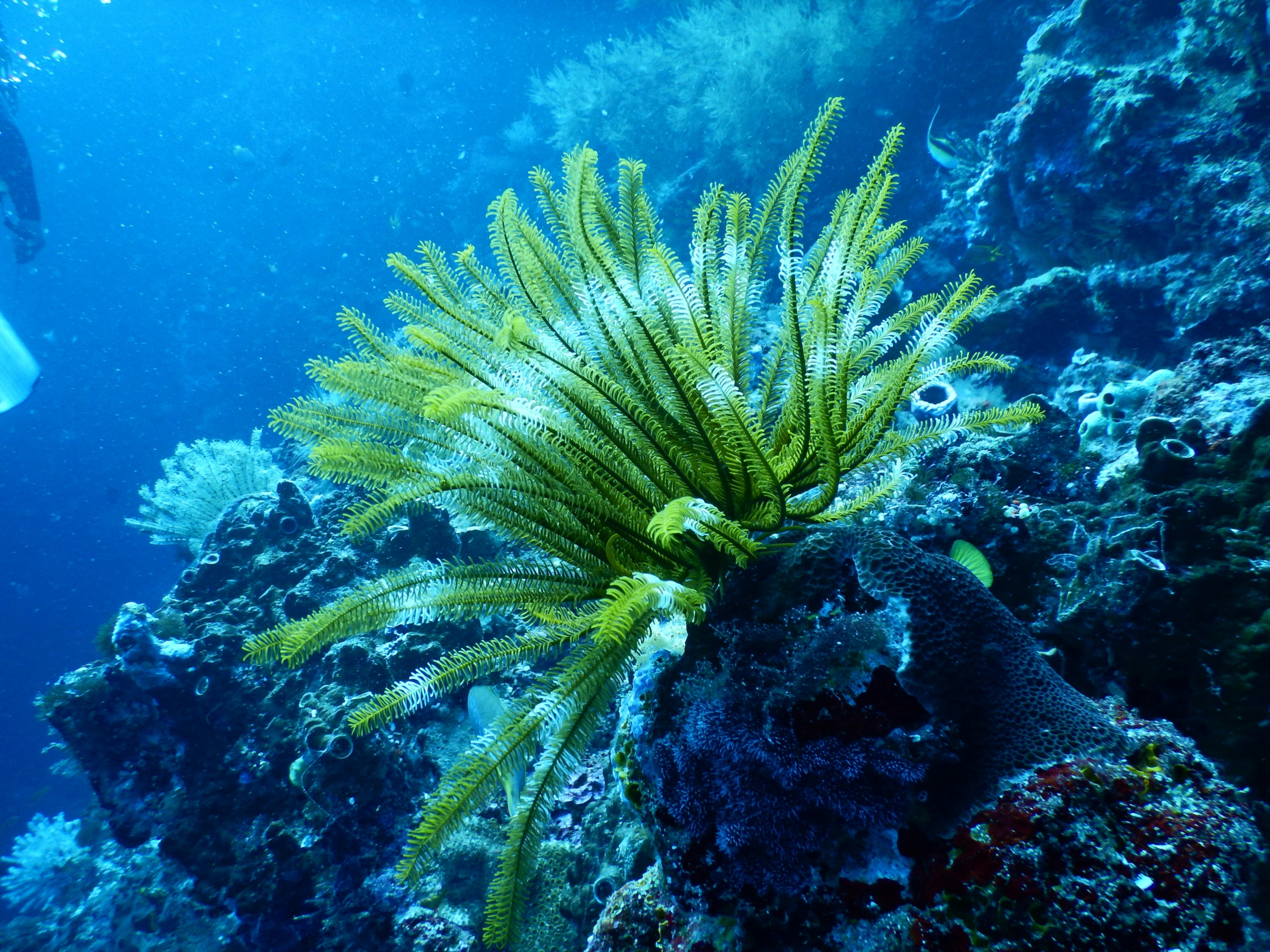

A little considered, but major consequence of the global shipping industry, attention has recently been turned to the issue of invasive species as local fishing industries have suddenly found themselves in dire straits due to interlopers like the Asian carp and zebra mussels.

Experts have previously warned that the new Arctic shipping routes opened up by melting sea ice may also mean new ways troublesome species can find new neighborhoods to invade, hitchhiking across half the globe on the hulls or in the ballast of large commercial vessels.

Ecologists are struggling to have all international ports enforce stricter polices to help prevent this spread, but Chawla and his colleagues argue that there are actually a finite number of ports in which efforts should be focused on.

Singapore, Chawla told New Scientist, is a prime example, as it contributes to about 26 percent of all invasive species flow in the Pacific Ocean's 818 ports.

"By assuming species-control policies were implemented on the top 20 percent of the most connected ports (like Singapore), we showed that it would be at least twice as difficult for species to propagate," he said.

The research was presented just last month, and should be considered preliminary findings until published in a peer-reviewed journal. Still, you can view an outline of the researchers' work here.

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.