In an effort to prevent the extinction of rare birds, millions of mosquitoes are being dropped from helicopters in Hawaii.

Honeycreepers Are Succumbing To Malaria

The indigenous, vividly colored honeycreeper birds of the archipelago are succumbing to malaria, which is spread by mosquitoes that were initially brought by American and European ships in the 1800s. The birds can perish from a single bite since they have not established immunity to the illness.

Thirty-three species of honeycreepers have gone extinct, and many of the 17 that are still in existence are in grave danger of going extinct in the next year or two if nothing is done. Now, using a novel tactic-releasing additional mosquitoes-conservationists are desperately attempting to save them.

Every week, 250,000 male mosquitoes carrying a naturally occurring bacteria that prevents conception are dropped from a helicopter onto the islands in the isolated archipelago. Ten million have been released thus far.

"The only thing that's more tragic is if [the birds] went extinct and we didn't try. You can't not try," said Chris Warren, the forest bird program coordinator for Haleakalā national park on the island of Maui.

With just one bird known to remain in the wild on Kauaʻi island, the population of the one honeycreeper, the Kauaʻi creeper, or ʻakikiki, has decreased from 450 in 2018 to five in 2023, according to the national park service.

Honeycreepers have an incredible diversity and canary-like song; each species has evolved with unique beak shapes, adapted to eating different foods, from fruit to nectar to snails. They are an important part of the ecosystem, helping to pollinate plants and eating insects.

Hawaii's birds have a very limited immune response to avian malaria since they did not evolve alongside it. The scarlet honeycreeper, or "i'iwi," for instance, has a 90% chance of dying if bitten by an infected mosquito.

The remaining birds typically reside at high altitudes above 1,200-1,500 meters (4,000-5,000 feet), where the temperature is too low for mosquitoes carrying the avian malaria parasite to survive. However, mosquitoes are shifting to higher altitudes as the temperature warms.

Read Also : Last 5 'Akikiki Bird Faces Possible Extinction as Non-Native Mosquitoes Bring Malaria to Hawaii

Incompatible Insect Technique

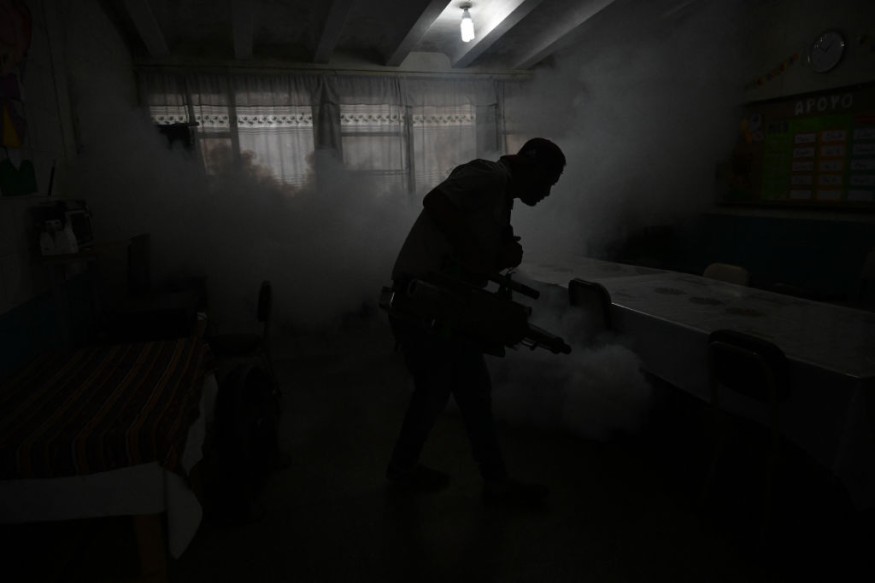

By releasing male mosquitoes with a naturally occurring bacteria that prevents the eggs of wild females they mate with from hatching, researchers are utilizing the incompatible insect technique (IIT).

Since female mosquitoes only mate once, the population is thought to eventually decline as a result. Most insects naturally harbor the bacteria Wolbachia, which is only able to procreate when two partners harbor the same strain of the germ.

Programs to apply the strategy to lower mosquito populations are still in place in Florida and California, having already proven effective in China and Mexico. This program's efficacy ought to be evident in the summer, when mosquito populations usually soar.

Dr. Nigel Beebe, from the University of Queensland, researched how the IIT technique works on other mosquito species and said that compared to employing pesticides that have significant off-target effects, it is far superior. In particular for matters like the preservation of endangered species.

Related Article : 6 Species of Hawaiian Songbirds Could Face Extinction in 10 Years Due to Climate Change and Rats

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.