According to research published in the January 23 issue of Nature Geoscience, Earth's inner core may have momentarily ceased spinning concerning the mantle and surface.

The Earth's inner core may now be rotating in the other way as part of a cycle that might last for around 70 years and affect the length of Earth's days and magnetic field; however, some scientists remain dubious about this.

Studying the Rotation

Geophysicist Xiaodong Song of Peking University in Beijing said, "We detect significant evidence that the inner core had been spinning faster than the surface, [but] by roughly 2009, it practically ceased." The direction of movement is now progressively shifting.

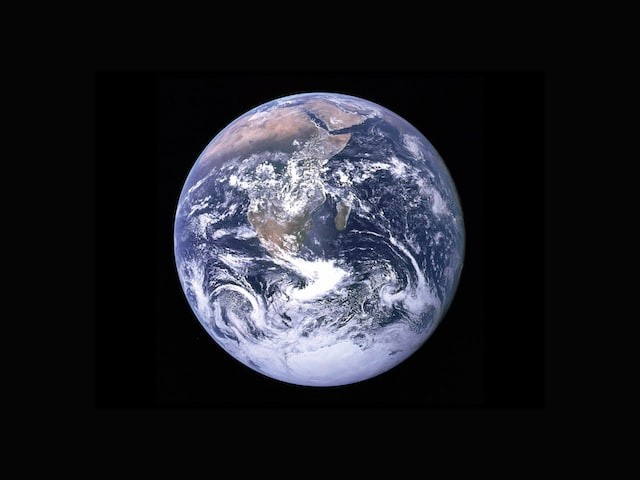

Although such a dramatic change can seem strange, Earth is unstable. You may penetrate the titanic mantle by drilling through the constantly moving crust. Here, enormous masses of rock flow violently over millions of years, sometimes upwelling to erode the crust above them. You can reach the Earth's liquid outer core by going deeper. Our planet's magnetic field is evoked here by flowing currents of molten metal. And at the center of that melt is a rotating, solid metal ball around 70% the size of the moon.

The inner core is this. According to studies, the magnetic force of the outer core may cause this solid heart to revolve within the liquid outer core. Additionally, scientists have suggested that the enormous gravitational force of the mantle may act as an irregular brake on the inner core's rotation, causing it to fluctuate.

Previous Researches

In 1996, the first indications of the inner core's varying rotation began to appear. Paul Richards, a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York, and Song, who was at Lamont-Doherty at the time, published research showing that for three decades, the time it took seismic waves from earthquakes to travel through the solid core of the Earth varied.

According to the researchers, the timing discrepancies are caused by the inner core rotating at a different rate than the mantle and crust. In a day, the globe rotates around 360 degrees. The researchers calculated that, on average, the inner core spins around 1 degree per year more quickly than the rest of Earth.

Other scientists, however, have cast doubt on that finding, with some arguing that the core either spins at a slower rate than Song and Richards estimated or didn't spin at all.

Using seismic data from throughout the world dating back to the 1990s, Song and geophysicist Yi Yang, both from Peking University, found an unexpected discovery in their recent research.

The researchers combed through data of doublet earthquakes in Alaska that date back to 1964. While the inner core seemed to revolve consistently for most of that period, the researchers claim it appears to have undergone another rotational reversal in the early 1970s.

According to Song and Yang, the inner core may fluctuate with a frequency of around 70 years, changing polarity about every 35 years. According to the researchers, these oscillations explain known 60- to 70-year changes in the length of Earth's days and the behavior of the planet's magnetic field since the inner core is gravitationally connected to the mantle and magnetically linked to the outer core. To identify the potential mechanisms, additional research is necessary.

However, not all scientists agree with this. According to geophysicist John Vidale of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study, Yang and Song "identif[y] this recent 10-year period [that] had less activity than previously, and I believe that's probably trustworthy." But Vidale claims that after that, things became tense.

He and a colleague revealed in 2022 that seismic signals from nuclear testing indicate the inner core may rotate in the opposite direction about every three years. Others have hypothesized that the inner core isn't moving at all. They assert that changes to the surface of the inner core may instead explain the variations in wave travel durations.

Final Inference

The differences between these investigations will presumably be easier to sort out via future observations, according to Vidale. He is not disturbed by the alleged chthonic halt at this time. He asserts that it has no bearing on life, but we don't truly know what's going on. It's up to us to solve the problem.

For more similar news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.