University of Arkansas biologists have improved scientists' understanding of animal vision, especially the colors they see, by collecting vision data from hundreds of vertebrates and invertebrates.

Recent Discovery

The researchers discovered that land-adapted animals could perceive more colors than water-adapted creatures. Animals acclimated to open terrestrial settings perceive more colors than those accustomed to forests.

However, a species' evolutionary history - particularly the distinction between vertebrates and invertebrates - substantially impacts which color it sees. When compared to vertebrates, invertebrates see more short wavelengths of light.

These findings were recently published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B by Biological Sciences doctoral student Matt Murphy and assistant professor Erica Westerman. Their article, "Evolutionary history limits species' ability to match color sensitivity to available habitat light," explains how environment, evolution, and, to some extent, genetic composition influence how and what colors animals see.

"For a long time, scientists have speculated that animal eyesight developed to match the hues of light prevalent in their habitats," Westerman said. "However, this hypothesis is difficult to prove, and there is still so much we don't know about animal vision." "Collecting data for hundreds of species of animals living in various habitats is a monumental task, especially when considering that invertebrates and vertebrates use different types of cells in their eyes to convert light energy into neuronal responses."

Wavelength Intensity

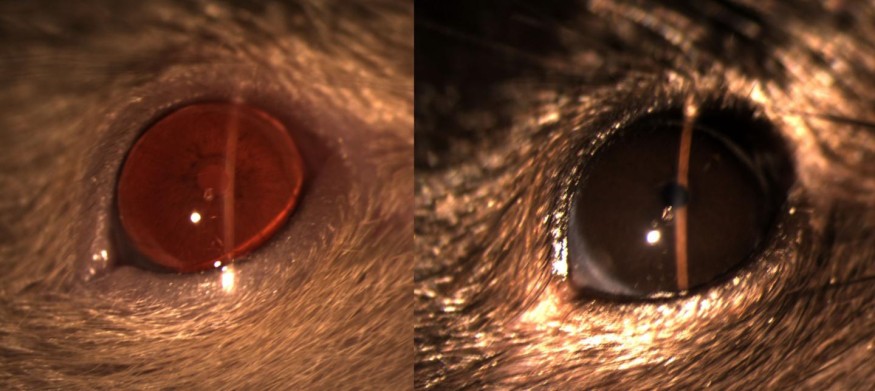

The wavelengths and intensity of light in a particular environment affect an animal's capacity to detect visual information. The spectrum of light an animal perceives is determined by the quantity and wavelength sensitivity of a class of retinal proteins called opsins, which range from ultraviolet to far red light.

On the other hand, invertebrates and vertebrates have phylogenetically unique opsins in their retinas, and scientists have yet to discover whether these opsins affect what animals perceive or how they adapt to their light surroundings.

Murphy and Westerman studied the eyesight of 446 animal species from four phyla. One of these phyla contained vertebrates or backboned creatures like fish and humans. Invertebrates, or creatures without backbones, such as insects, squid, and jellyfish, were found in the remaining phyla.

The study found that while animals adapt to their surroundings, their ability to adapt is biologically limited. While both vertebrates and invertebrates employ the same cell type, opsins, to see, they construct these cells in distinct ways. This physiological difference between vertebrates and invertebrates, known as ciliary opsins in vertebrates and rhabdomeric opsins invertebrates, could explain why invertebrates are better at seeing short wavelength light. However, their habitat should select for vertebrates to see short wavelength light.

Role of Genetics

According to Westerman, the discrepancy might be attributable to stochastic genetic changes in vertebrates but not invertebrates. These mutations may also reduce the amount of light that animals can see.

"Our work addresses some essential concerns, but it also raises new ones," Murphy said. "We can do more to analyze variations in the anatomy of vertebrate and invertebrate retinae, or how their brains interpret visual information differently, and these are intriguing topics."

For the most recent updates from the animal kingdom, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.