Octopus matriarchs are known for their imminent self-harm tendencies after they give birth to their offspring.

The self-destructive behavior of mother octopuses has been in the twilight zone since it was first discovered.

In a ground-breaking study, scientists explored the self-injury behavior of a female octopus, and for the first time, understood that certain biochemical processes are responsible.

The discovery highlights the octopus deaths as a biological necessity rather than an abnormal biological phenomenon.

Octopus Self-Destruction

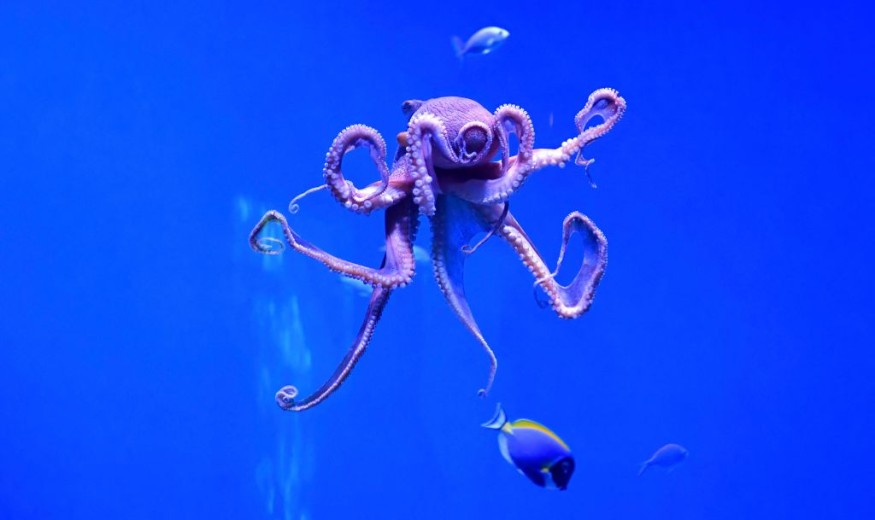

An octopus (Octopoda) is a soft-bodied marine invertebrate belonging to the class Cephalopoda, like cuttlefish and squids, and the phylum Mollusca.

Although most octopus has a lifespan of almost a year, an octopus mom falls to a high mortality rate due to the strange behavior after laying its eggs and tending to them.

Some of the following self-injury actions are intentional starvation, color, and muscle tone loss, rubbing against the seafloor's gravel, eating their own arms, and causing scarring and lesions on their bodies.

While the mysterious behavior has shrouded the minds of scientists for years, a new study used the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) as a sample model to understand once and for all the physiology behind the behavior.

In the new paper published in the journal Current Biology on May 12, scientists from various universities in the United States, including the University of Chicago and the University of Washington, concluded octopus maternal behaviors and death are influenced by hormones or steroidal pathways.

The new study started with the foundation that the lifespan and reproduction of the cephalopods are governed by two optic glands, its principal neuroendocrine center.

Unlike the vertebrate pituitary gland which secretes hormones and other chemicals throughout the body, the octopus gland has nothing to do with the vision of the eight-legged invertebrates; it was only named as such due to its location between the animal's eyes.

Also Read: Octopus Ancestors Among the First Animals on Earth, Dating Back to 509 Million Years Ago!

Optic Glands and Chemical Compounds

The study claimed these optic glands produce the following chemical pathways which dictate the mother octopus' reproductive behavior:

- Progesterone

- Pregnenolone

- Bile Acids

- 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC)

The first two substances progesterone and pregnenolone are reportedly common since it is also produced by other animals during reproduction.

Meanwhile, bile acids support the absorption of dietary fats.

Furthermore, 7-DHC is also produced by many vertebrates, including humans, which uses the chemical compound to generate cholesterol and vitamin D.

However, scientists believed that 7-DHC is responsible for the behavior relating to the octopus self-destruction behavior.

Dr. Z. Yan Wang, the study's author and professor at the University of Washington, and other researchers have suspected that 7-DHC is possibly a significant factor in triggering the self-harm behavior that leads to death, according to The New York Times.

Wang stated that 7-DHC amongst octopuses and other invertebrates is the same as in humans.

While the molecules are the same, the lead author acknowledges that discovery is "remarkable" that the same chemical compound is shared by various animals that are very distant from each other, as cited by The New York Times.

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.