According to an international team led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography researchers at UC San Diego, climate change affects the mechanics of surface ocean circulations, causing them to become quicker and thinner.

Changing Ocean Mechanics

Since 1880, the sea level has risen at a pace of around six-tenths of an inch per decade when measured throughout all of the world's seas. In recent years, growth has quickened to more than an inch each decade. The rate at which the sea level rises or falls concerning the land varies by area.

These alterations may have a ripple effect in the water, altering both the transfer of nutrients required by species and the transport of microbes. Swifter currents may also impact the mechanisms through which the ocean takes carbon and heat from the atmosphere, protecting the world from overheating.

"When we heated the ocean surface, we were shocked to observe that surface current accelerated across more than three-quarters of the world's seas," said study lead author Qihua Peng, who just joined Scripps Oceanography as a postdoctoral researcher.

Looking at Various Factors

The study, published in the journal Science Advances on April 20th, offers insight into a previously unknown factor that influences the speed of global ocean currents. It contributes to the argument over whether or not currents are speeding up due to global warming.

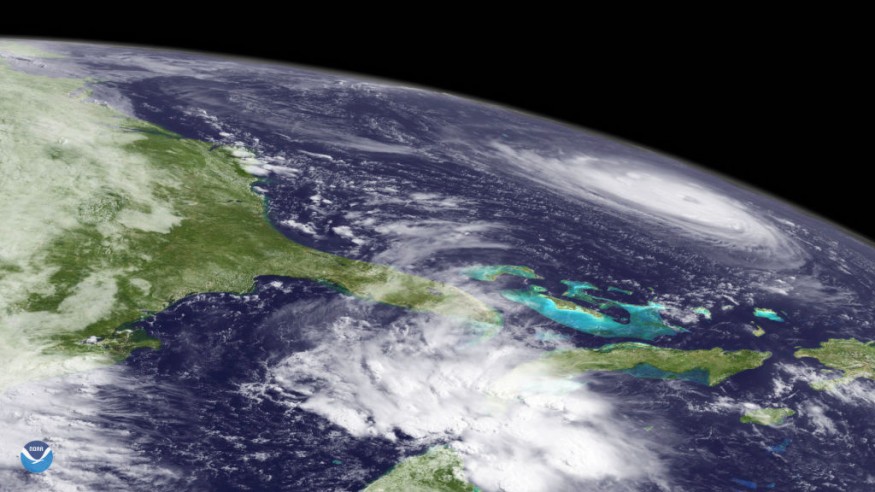

The primary element investigated by scientists to characterize and forecast the speed of currents has been the wind. Still, the study team utilized a worldwide ocean model to mimic what occurs when sea surface temperatures also rise. They discovered that when the temperature increases, the upper layers of water become lighter. In more than three-quarters of the world's oceans, the increasing density differential between the warm surface layers and the cold water beneath confines the swift ocean currents to a narrower layer, forcing surface currents to speed up. The slowing of ocean circulation was linked to the increasing speed of spinning ocean currents known as gyres. According to the researchers, the trend was directly related to ever-increasing quantities of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Insights

"Our research leads to a path ahead for exploring ocean circulation change and assessing uncertainty," said Shang-Ping Xie, a Scripps Oceanography climate modeler whose work is supported by the National Science Foundation.

In most seas limited by land, currents are structured into gyres. The Southern Ocean, which encircles Antarctica, is an outlier. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the world's greatest in terms of volume transfer, thanks to howling westerly winds. Last year, Scripps scientists discovered that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is speeding up based on ocean and satellite studies.

"As the temperature warms, our model anticipates the accelerated Antarctic Circumpolar Current," Xie added.

Dongxiao Wang of Sun Yat-Sen University in China and experts from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, and UC Riverside were among the study's co-authors.

For more Environmental News, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.