The Arctic is losing sea ice at an alarming rate. Less ice means more open water, which means more gas and aerosol emissions from the ocean, warming the atmosphere and making it cloudier.

Aerosol Observation

When University of Michigan aerosol scientist Kerri Pratt's group collected aerosols from the Arctic atmosphere in the summer of 2015, Rachel Kirpes, a doctorate student, noticed something unusual: aerosolized ammonium sulfate particles didn't seem like ordinary liquid aerosols.

Kirpes discovered that ammonium sulfate particles, which should have been liquid, were solid while working with fellow aerosol scientist Andrew Ault. The team's findings were reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Solid Aerosols

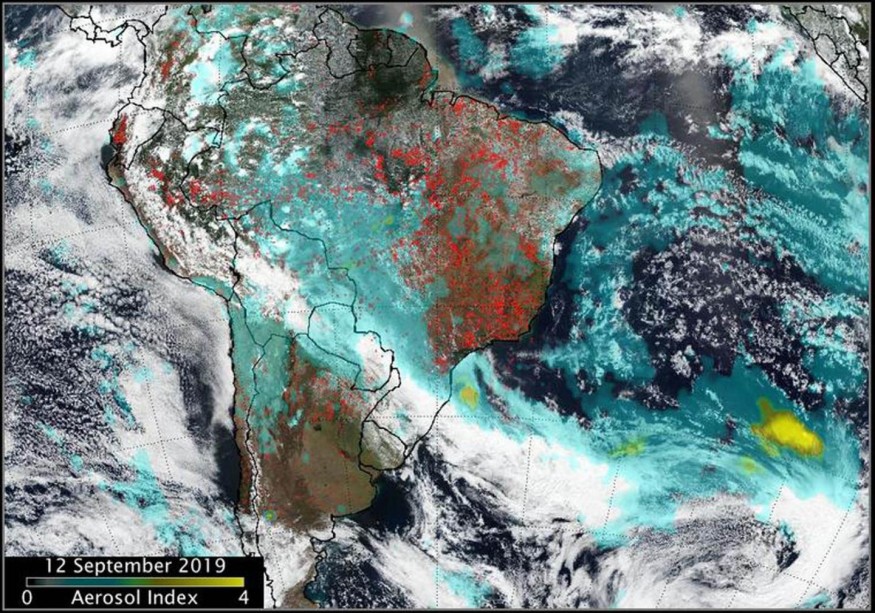

Solid aerosols have the potential to alter cloud formation in the Arctic. Researchers anticipate seeing more of these unusual particles created from marine emissions coupled with ammonia from birds as the Arctic loses ice, influencing cloud formation and climate. Understanding the features of aerosols in the atmosphere is also crucial for improving climate models' capacity to predict the present and future climate in the Arctic and beyond.

"Because the Arctic is warming faster than anyplace else on the planet, these particles may become more relevant as we have more emissions from open water in the atmosphere," said Pratt, an associate professor of chemistry and earth and environmental sciences. "These kinds of observations are essential since there are so few of them that we can even test the correctness of Arctic atmospheric models."

When you make measurements with few observations, you might get surprises like this. These particles didn't like anything we'd seen before in the literature, the Arctic, or anyplace else on the planet.

The aerosols measured up to 400 nanometers in diameter, nearly 300 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. According to Ault, an assistant professor of chemistry, aerosols in the Arctic are often thought to be liquid.

Turning Liquid

The particle turns liquid when the relative humidity of the atmosphere hits 80%, which is roughly the level of a humid day. When you dry the aerosol out again, it takes around 35 to 40 percent relative humidity to transform it into a solid. Researchers anticipate finding liquid aerosols since the air above the Arctic Ocean - or any ocean - is humid.

However, they discovered relatively novel phenomena in which a tiny particle collides with our droplets when the humidity is below 80 percent but above 40 percent. Ault said that this essentially offers a surface for the aerosol to solidify and become solid at a greater relative humidity than predicted.

These particles resembled marbles rather than droplets. That's critical, especially in a place where there haven't been many observations, since those particles might wind up functioning as cloud seeds or causing reactions to occur on them.

Characteristics

According to the study, the size, content, and phase of atmospheric aerosols also affect climate change through water absorption and cloud formation.

"It is our responsibility to continue to assist modelers in refining their models," Ault stated. "It's not that the models are incorrect; they just require additional data as events on the ground change, and what we witnessed was entirely unexpected."

In August-September 2015, Pratt's team collected aerosols in Utqia?

Utqiagvik

Utqiagvikis Alaska's farthest northerly point. To achieve so, they employed a multistage impactor, which is a device with numerous stages that gather particles based on their size. Kirpes used microscopy and spectroscopic techniques to evaluate the composition and phase of particles smaller than 100 nanometers in size in Ault's lab.

"We wouldn't be detecting these particles if we went back many decades when there was ice along the beach, even in August and September," Pratt said. "We're observing the implications of this climate already changing." They need to replicate reality in models that represent clouds and the atmosphere, which are crucial for understanding the energy balance of the Arctic atmosphere, which is changing at a quicker rate than anyplace else.

Read also: Gloom Reality: Even the Most Daring Technologies Can No Longer Reverse Impacts of Climate Change

For similar news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.