Last month, an underwater volcano in the South Pacific erupted, shattering two records: the volcanic plume reached greater heights than any other eruption ever recorded by satellite.

The Tonga volcanic eruption also produced an unprecedented number of lightning strikes - nearly 590,000 for three days, according to Reuters.

"The combination of volcanic heat and the volume of superheated moisture from the ocean made this eruption exceptional; it was like hyper-fuel for a mega-thunderstorm," said Kristopher Bedka, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Langley Research Center who studies extreme storms.

Eruptions Seen From Space

According to Nature, the volcano, known as Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, is located about 40 miles (65 kilometers) north of Nuku'alofa, Tongan capital, and is part of the Tonga-Kermadec volcanic arc, a line of primarily underwater volcanoes that runs along the western edge of the Pacific Plate of Earth's crust.

Reuters reported that the eruption began on Jan. 13, resulting in explosions that broke the water's surface and a big lightning storm. Then, on Jan. 15, surging magma from Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai collided with seawater above the volcano, causing a tremendous explosion.

Such explosive eruptions can occur when magma rapidly warms water into steam, which then expands fast; bubbles of volcanic gas trapped inside the magma also serve to propel these spectacular explosions up and out of the water.

Producing Dangerous Gases

Underwater volcanic eruptions don't usually send massive plumes of gas and particles into the air, but the one on Jan. 15 was an exception.

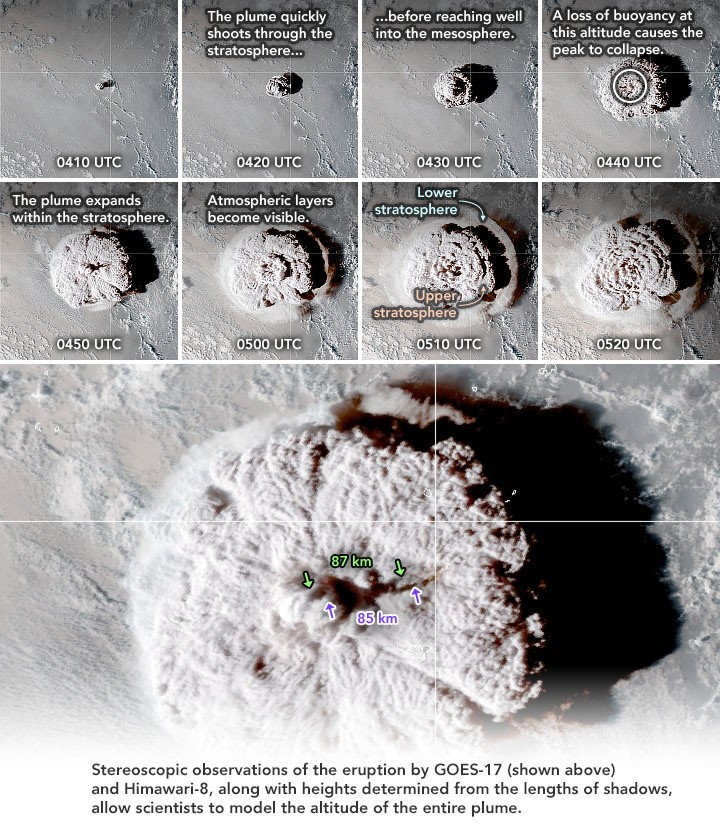

The unusual eruption was captured from above by two weather satellites: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite 17 (GOES-17) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Himawari-8. Scientists at NASA's Langley Research Center calculated how far the plume penetrated the atmosphere.

"We were able to generate a three-dimensional picture of the clouds from the two perspectives of the satellites," Konstantin Khlopenkov, a NASA Langley scientist, said in a statement.

According to the NASA statement, the plume climbed 36 miles (58 kilometers) into the air at its maximum point, piercing the mesosphere - the third layer of the atmosphere. A secondary outburst from the volcano spewed ash, gas, and steam more than 31 miles (50 kilometers) into the air after an earlier blow created this towering column.

Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted in 1991, sending a plume 22 miles (35 kilometers) above the volcano. Until the current Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption, that 1991 event held the record for the biggest recorded volcanic plume in satellite records.

When the tops of these plumes reached the mesosphere, they immediately became gaseous. However, gas and ash from the volcano collected and expanded to cover an area of 60,000 square miles in the stratosphere below (157,000 square kilometers).

"The eruption plume looks to have caused waves in the atmosphere when it entered the stratosphere and extended outward," Chris Vagasky, a meteorologist at Vaisala, an environmental technology business, told Reuters.

Vagasky and his colleagues continue investigating the eruption's lightning activity, and he's particularly curious about how these air waves altered the pattern of lightning strikes.

The team utilizes data from GLD360, Vaisala's ground-based lightning monitoring network, to investigate the lightning. According to Reuters, roughly 400,000 of the nearly 590,000 lightning strikes that occurred during the eruption came within six hours after the detonation on Jan. 15.

Before the eruption in Tonga, the greatest volcanic lightning event in Vaisala's records occurred in Indonesia in 2018, when Anak Krakatau erupted, resulting in 340,000 lightning strikes over a week. According to the scientists, almost 56 percent of the lightning impacted the land or ocean's surface, with over 1,300 strikes landing on Tongatapu, Tonga's biggest island.

Lightning

There were two types of lightning. Dry charging, in which ash, pebbles, and lava particles collide in the air and swap negatively charged electrons, is one sort of lightning.

According to Reuters, the second sort of lightning was created by "ice charging," which occurs when the volcanic plume reaches heights where water may freeze and form ice particles collide.

Both of these processes cause electrons to build upon the undersides of clouds, which subsequently lead to higher, positively charged parts of the clouds or positively charged portions of the land or sea below, resulting in lightning strikes.

For more Space news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.