Rarely does a country get the opportunity to spell forth its national goals and draft a new constitution. The climate and ecological catastrophe hardly seldom play a prominent role.

That is, until now, in Chile, where a national renaissance is taking place. After months of protests over social and environmental issues, 155 Chileans were voted to create a new constitution in the face of a "climate and ecological emergency," which they have proclaimed.

Their efforts will significantly impact how this country of 19 million people is governed. It will also influence the fate of lithium, a soft, shiny metal found in the saline seas beneath this huge ethereal desert adjacent to the Andes Mountains.

Lithium Mining

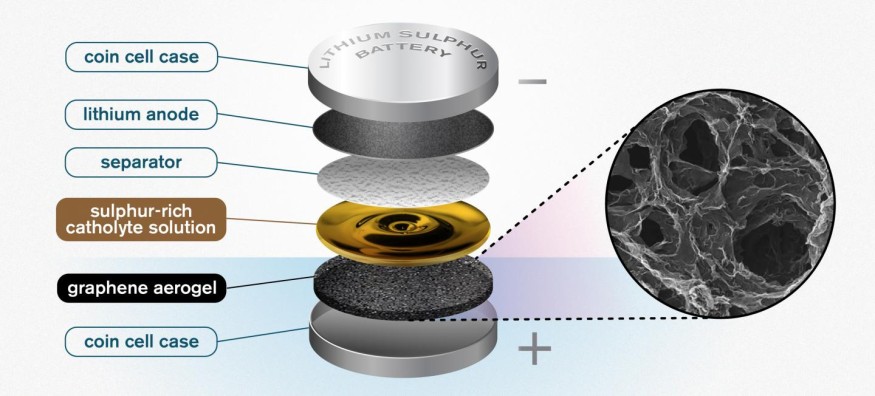

Lithium is an essential part of batteries. Lithium demand - and prices - are on the rise as the world economy looks for alternatives to fossil fuels to halt climate change.

Mining corporations in Chile, the world's second-largest lithium producer after Australia, are eager to boost output, as do politicians who consider the mining as critical to the country's economic success. They confront growing criticism from Chileans who claim that the country's economic model, which is centered on extracting natural resources, has imposed a high environmental cost and has failed to distribute the advantages to all inhabitants, particularly the country's Indigenous people.

Related Article : Fight Against Lithium Mining on Sacred Land Rages in Nevada

Constitutional Convention

As a result, the Constitutional Convention will have to select what type of country Chile wishes to be. Members of the convention will deliberate on various issues, including how mining should be governed and what role local communities should have in mining. Should Chile's presidential system be preserved? Should nature be allowed to have rights? What about the next generation?

Global Problem

Nations all across the globe are grappling with similar issues as they strive to address the climate catastrophe without repeating previous mistakes - in the forests of central Africa, in Native American territory in the United States. For Chile, the issue now can influence the country's constitution. "We must presume that human action creates harm; how much harm do we wish to inflict?" "Cristina Dorador Ortiz, a microbiologist and member of the Constitutional Convention, researches the salt flats. "How much harm is enough to live a happy life?"

Chile's present constitution was drafted in 1980 by officials appointed by Augusto Pinochet, the country's military dictator. It authorized mining ventures and the purchase and sale of water rights.

Chile developed by using its natural resources, including copper, coal, salmon, and avocados. Even as it became one of Latin America's wealthiest countries, complaints about inequality grew. Mineral-rich regions began to be designated as "environmental sacrifice zones." Rivers started to dry up.

Starting in 2019, rage turned into massive protests. A national vote chose a diverse panel to update the constitution.

Also Read : 200 Health Journal Calls Out World Leaders to Address How Climate Change Causes Health Hazard

For more environmental news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.