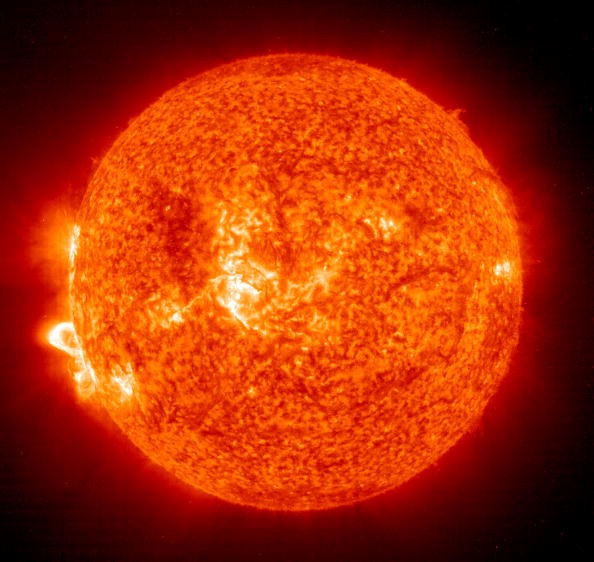

The sun occasionally emits massive outbursts of particles and radiation that may cause havoc on Earth.

Scientists researching these eruptions and how they influence our world have focused on a single, seemingly apex occurrence for more than 150 years: the Carrington Event of 1859.

Here, a solar explosion slammed onto Earth, injecting enough energy into the planet's magnetic field to trigger a tremendous geomagnetic storm that produced stunning auroral displays but also ignited electrical fires in telegraph wires.

The Carrington Event

Because electronic infrastructure was so rudimentary at the time, the storm was dismissed as a mere annoyance. However, experts now see the Carrington Event, along with another storm of equal size in 1921, as a forewarning of future disasters.

Both storms, however, pale in contrast to a historic megastorm of colossal proportions that happened about A.D. 775 and was likely 10 to 100 times greater, as revealed in 2012. Nicolas Brehm of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich adds, "It was really, truly astonishing. We never imagined something this big could happen."

Scientists speculated that the ancient megastorm was caused by a once-in-10,000-years "superflare" bursting from the sun, even thousands of times more intense than a typical solar flare.

A direct strike by such a superflare now would very certainly be catastrophic for our modern, globally-connected society. Fortunately, they're uncommon occurrences.

Related Article : Expert Warns 'Situation Worse than Covid' if Government Ignores Solar Flare Defense

Probability of It Happening Again

Scientists report the probable finding of two terrifyingly powerful solar events in a preprint study headed by Brehm, published on Research Square and submitted to Nature Communications.

The first happened in 7176 B.C. when nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes gave way to agrarian settlements, and the second occurred in 5259 B.C. when the world emerged from its most recent ice age. Both occurrences are considered to be at least as powerful as the one in 775 A.D., making the three the most powerful solar flares ever recorded. Scientists have been looking for more severe occurrences like the eighth century for the past decade.

The team led by Brehm is the first to discover some. "It's a fantastic accomplishment," says Fusa Miyake of Nagoya University in Japan, who conducted a study that found the 775 events in 2012. As a result, superflares are now referred to as "Miyake events" by scientists.

Brehm and his colleagues were fortunate in their research. Preliminary evidence for a beryllium 10 spike was initially discovered in ice cores for the event in 7176 B.C.

Following up with tree rings, the researchers found a carbon 14 increase. Bayliss had identified a gap in archaeological evidence during this time period for the incident in 5259 B.C.

Another increase was discovered when the scientists looked at carbon 14 data in tree rings from this time period. Brehm explains that "we found this tremendous increase" for both dates, which is identical in scale to the spikes Miyake saw in the samples that clinched the A.D. 775 event.

"However, they're far too uncommon to have such a high frequency. It doesn't seem to make as much sense as the solar explanation."

He contends that such massive, regular increases were more likely the outcome of increasing solar activity, potentially accompanied by a geomagnetic storm similar to but considerably more intense than the Carrington Event.

According to Bayliss, "the Carrington Event isn't even detectable" in tree rings and ice cores, implying that it was little in contrast.

A Carrington-Like Event Today

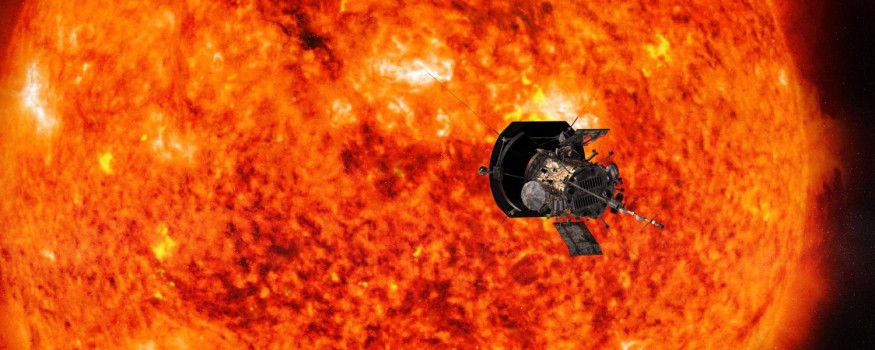

The main concern is that if such an event occurred now, it would be catastrophic for satellites in orbit and terrestrial infrastructure.

For example, despite being far smaller than the Carrington Event, a geomagnetic storm in March 1989 produced a 12-hour blackout in Quebec when it overwhelmed the whole province's electrical infrastructure.

A geomagnetic storm caused by a Miyake event today would have far more extensive consequences, including the possibly catastrophic power grid and satellite outages.

According to Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi of the University of California, Irvine, A Carrington Event- level storm today might create an "Internet catastrophe." The energetic particles produced by such a storm may knock out underwater cables connecting countries, causing global Internet traffic to be disrupted for weeks or months.

A Monumental Problem

According to Abdu Jyothi, a calamity like this might cost $7 billion per day in the United States alone. Something more powerful, such as a Miyake event, may produce nearly unquantifiable damages.

"For anything of the Carrington magnitude, we might be able to recover," Abdu Jyothi adds, noting that his data will not be wiped.

"I'm not sure what I'd do with something 10 or 100 times stronger. That hasn't been replicated, as far as I know. I believe it will result in severe data loss. We may lose all of our documents, financial information, and vital health information, with no way of recovering."

For more cosmic news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.