Paleontologists from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences recently discovered two new species of ancient animals that had lived in now northeastern China from 120 million years ago.

The two species were said to be distantly related and has evolved their 'digging traits' independently. They were both classified as cretaceous mammaliamorphs that lived the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota, a home to great diversity of animals, from dinosaurs and insects to plants, about 120 million years ago in northeastern China, the last common ancestor of Tritylodontidae and Mammalia, and first represented "scratch diggers" in this ecosystem.

The discovery had shed light on the fossoriality and evolutionary development of mammaliamorphs.

Digging Traits of Burrowing Mammals

Typically, burrowing mammals 'dig for a living'. Other times, it is to protect them from getting eaten by predators or maintain a certain temperature suitable for them. Recent discovery suggests that the two new-found species share a convergent feature, developing similar characteristics necessary for their survival.

"These two fossils are a very unusual, deep-time example of animals that are not closely related and yet both evolved the highly specialized characteristics of a digger," said lead author Dr. Fangyuan Mao.

Previous studies use fossil records of burrowing animals or 'burrowers' as they 'make a great case' in understanding convergent evolution and how they adapt a certain physique for digging as a coping mechanism to habitat influences or changes.

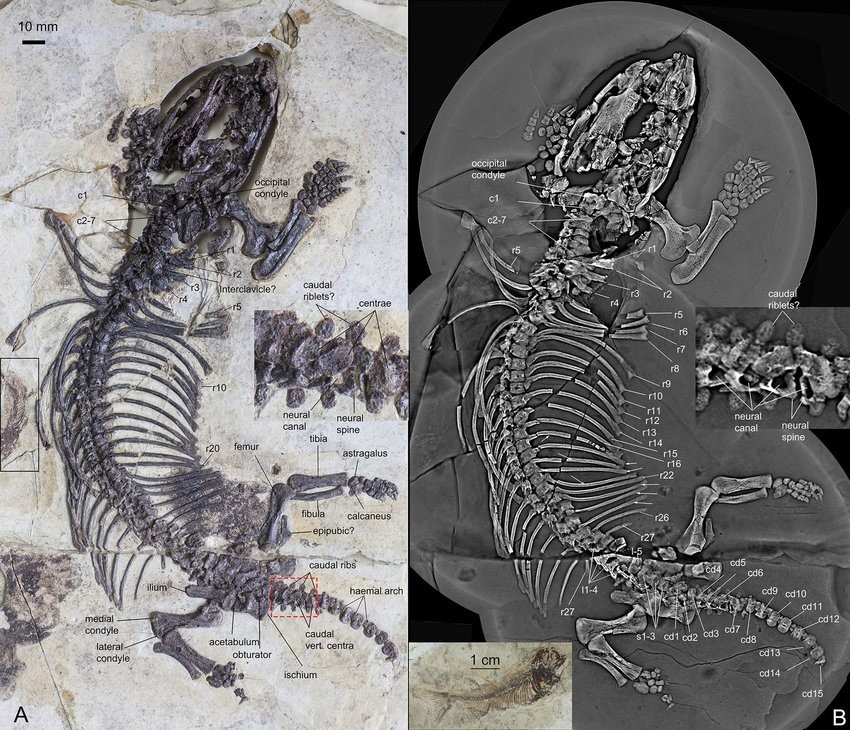

In the new research, it was found that the first species was a foot long mammal-like reptile identified as a tritylodontid, known as Fossiomanus sinensis. The animal was believed to have recently came first into existence in Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. On the other hand, the second species was classified as a seven-inch long eutriconodontan, a distant cousin of modern placental mammals and marsupials commonly existed in the biota.

First Convincing Evidence for Fossorial Life

The research team were convinced that the two discovered species served as the 'first convincing evidence for fossorial life in those two groups'. Dr. Mao added that they were also the first case of scratch diggers in the Jehol Biota.

An unusual feature found common in the two fossils is their elongated vertebral column. Both species show an increased number of presacral vertebrae. The Fossiomanus had 38 vertebrae, 12 times higher than the usual number, while Jueconodon had 28, which is rare because mammals typically only have 26 vertebrae from the neck to the hip.

Paleontologists seek understanding from recent studies in developmental biology to determine how these animals had acquired their elongated axial skeleton. The number and shape of the vertebrae found in the fossils could also be attributed to gene mutations during these mammals' early embryonic development. The researchers noted that these variation in number of vertebrae are also prevalent in other modern species of mammals such as in elephants, manatees, including hyraxes.

Lastly, interaction of developmental mechanisms and natural selection could be responsible for the diverse phenotypes the independently evolving mammaliamorph.

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.