The ocean is home to a wide variety of bizarre invertebrates that never cease to show the wonders of evolution. And recently, scientists have discovered that one rare mollusk shows an even rarer trait: Metal teeth.

At least, those are the findings from a recent study on the gumboot chiton. Scientists have just confirmed that black protrusions from its radula (a tongue-like organ used to scrape rocks) are actually made of magnetite (a unique form of iron mineral that is surprisingly tough for something grown out of a biological organism).

Implications of iron teeth in mollusks

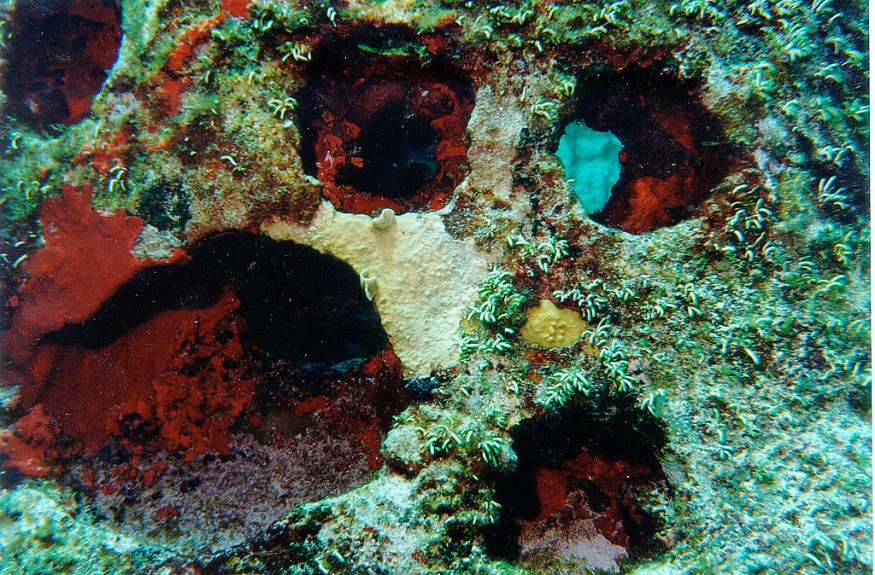

Also known as the gumboot chiton, it belongs to a type of mollusk characterized by overlapping shells and no visible head unlike snails and slugs. At first glance, it seems unremarkable with its basic, light brown color and docile behavior. It spends its life underwater, eating algae and rocks along the ocean floor.

But in order to do this, scientists presumed that its teeth must still be quite hard (even for its relatively small size). Using high-energy X-rays, they got a much closer look at them and basically confirmed that this drab mollusk's spiky rock-scraping fangs were 100% metal.

The implications of this study may have definitely widened the possibility of organisms naturally evolving metallic parts or at least certain minerals once thought to only occur in inorganic matter (such as soil and rocks).

Only a few other species have shown this possibility. For instance, the scaly foot snail is also another organism that has incorporated metal into both its shell as well as certain outer sclerites. But as few as they are, each one could be said to explain a lot of genetic mysteries as to how an organism could go as far as to assimilate metallics into organic bodies to survive harsh environments.

Mollusk's iron teeth as model for new nanomaterial

The study also allowed the scientists to get a closer look at what other minerals could be affixing the magnetite teeth to the fleshy radula. And based on what they discovered, they had even gone so far as to try and replicate some of these minerals.

Using a bold, 3D printing experiment, the scientists further suggested that the experimental nanomaterials could have a number of engineering applications (particularly in technologies that need a very fine transition between hard and soft moving parts).

Yet as impressive as these possibilities are, mollusks like the wandering meatloaf and the scaly foot snail are still exposed to the ever-present dangers of degrading marine environments. Problems like global warming are increasing ocean temperatures that are killing the algae that the mollusks need to survive, as well bleaching the coral reef ecosystems in which they live.

Other threats like underwater mining are also indirectly killing these rare invertebrates while destroying their homes. This has resulted in many scientists struggling to conduct studies on how they perform their amazing adaptations with metallic compounds. And unless action is taken, any more secrets they could reveal may be lost forever.

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.