Humans have a higher density of sweat glands found in their skin than chimps and macaques.

In fact, they have 10 times that of chimps and macaques. Penn Medicine experts have now learned how this unique, hyper-cooling feature developed in the human genome.

Researchers found that the higher density of sweat glands in humans is due to cumulative improvements in a regulatory area of DNA called an enhancer region that drives the expression of a sweat gland-building gene, explaining why humans are the sweatiest of the Great Apes.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Studying Sweat Glands

Yana Kamberov, Ph.D., an assistant professor of genetics at Penn Medicine, said, "This is one of the clearest cases I've ever seen of pinpointing the genetic origin for one of the most drastic and distinctively human evolutionary characteristics; as a whole." "This type of study is significant not just because it demonstrates how nature works to generate species diversity, but also because it provides us with insights into human biology that are often unavailable in other ways.

Basically through studying how to tweak the biological system in a way that is potentially useful, without destroying it."

Related Article : Better Primates? Humans Evolved to be More Water Efficient Than Nearest Animal Kin

Temperature Control

The high density of sweat glands, also known as eccrine glands, in humans is thought to be an ancient evolutionary adaptation, according to scientists. This adaptation, combined with early hominins' lack of fur, which allowed them to cool off by sweat evaporation, is thought to have made it easier for them to run, hunt, and otherwise live in the humid, treeless African savannah. A very different environment than the jungles inhabited by other ape species.

EN1 Genes

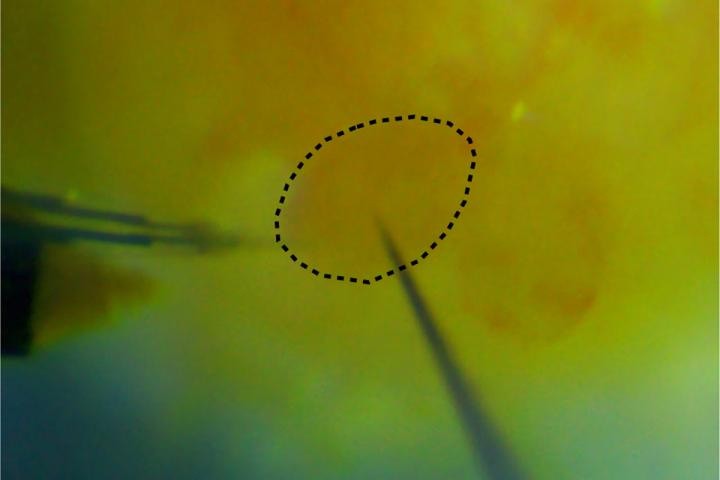

In a 2015 study, Kamberov discovered that the expression frequency of a gene called Engrailed 1 (EN1 in humans) influences the density of eccrine glands in mice. EN1 is a transcription factor protein that acts during development to cause immature skin cells to form eccrine glands, among other things. Because of this property, Kamberov and colleagues speculated that humans may have evolved more sweat glands in their skin is by genetic changes that increased EN1 development in the skin.

Enhancer regions, which are nearby regions of DNA where factors that activate the gene can bind and help drive the gene's expression, can also influence a gene's function. Kamberov and her colleagues discovered an enhancer region called hECE18 that boosts the development of EN1 in the skin, causing more eccrine glands to form. The researchers found that the human form of hECE18 is more successful than the ape or macaque forms, implying that human EN1 output is higher.

Prior research has traditionally linked evolved human-specific characteristics, such as expression, to complex genetic modifications affecting various genes and regulatory regions. Kamberov and her colleagues' findings, on the other hand, indicate that the human "high-sweat" phenotype developed at least in part as a result of repetitive mutations to a single regulatory region, hECE18. This suggests that this single regulatory feature may have played a role in the slow evolution of higher eccrine gland density during human development.

Though the research is primarily a feat of fundamental biology that sheds light on human evolution, Kamberov believes it would also have long-term medical implications.

The Body Managing Itself

"Severe wounds or burns kill sweat glands in the skin, and we don't know how to rebuild them," she said. "But this research takes us closer to learning how to do that." "The next step in this study will be to find out how the various activity-enhancing mutations in hECE18 interact with one another to enhance EN1 expression and to use these biologically important mutations as starting points for determining which DNA-binding factors bind at these sites. Essentially, this gives us a clear molecular pathway to discover the upstream factors that cause skin cells to start producing sweat glands by activating EN1 expression."

For more biological news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.