Traditionally, people think that lungs and limbs are key contrivances that come with the transition from water to land by vertebrates.

But indeed, 50 million years ago, the genetic foundation of air-breathing and limb movement was already developed in our fish ancestors. This, according to the latest genome mapping of prehistoric fish carried out, among others, by the University of Copenhagen. The latest research modifies our interpretation of a crucial milestone in our own experience of evolution.

For a while, evolutionists have theorized that humans, and all other vertebrates, evolved from prehistoric fishes.

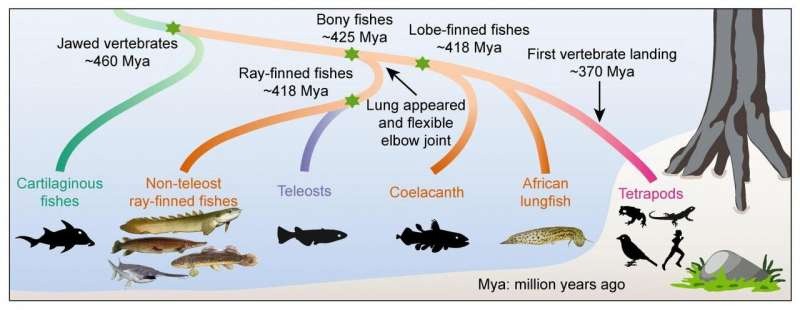

The traditional understanding was that certain fish shimmied to the land as small, "lizard-like" creatures known as tetrapods around 370 million years ago.

According to this interpretation, by turning their fins to limbs and breathing underwater to air-breathing, our fish ancestors come out of the water to land.

However, limbs and lungs are not innovations that appeared as recently as once believed. Our common fish ancestor that lived 50 million years before the tetrapod first came ashore already carried the genetic codes for limb-like forms and air-breathing needed for landing. These genetic codes are still present in humans and a group of primitive fishes.

This has been demonstrated by recent genomic research conducted by the University of Copenhagen and its partners.

The new research reports that the evolution of these ancestral genetic codes might have contributed to the vertebrate water-to-land transition, which changes the traditional view of the sequence and timeline of this big evolutionary jump.

The study has been published in the scientific journal Cell.

"The water-to-land transition is a major milestone in our evolutionary history. The key to understanding how this transition happened is to reveal when and how the lungs and limbs evolved. We are now able to demonstrate that the genetic basis underlying these biological functions occurred much earlier before the first animals came ashore," stated professor and lead author Guojie Zhang, from Villum Centre for Biodiversity Genomics, at the University of Copenhagen's Department of Biology.

A group of ancient living fishes might hold the key to explain how the tetrapod ultimately could grow limbs and breathe on air. The group of fishes includes the bichir that lives in shallow freshwater habitats in Africa.

These fishes differ from most other extant bony fishes by carrying traits that our early fish ancestors might have had over 420 million years ago.

And the same characteristics are also present in, for example, humans. Through genomic sequencing, the researchers found that the genes needed to develop lungs and limbs have already appeared in these primitive species.

Impact of the Study

"The study enlightens us with regards to where our body organs came from and how their functions are decoded in the genome. Thus, some of the functions related to lungs and limbs did not evolve when the water-to-land transition occurred but are encoded by some ancient gene regulatory mechanisms already present in our fish ancestor far before landing. Interestingly, these genetic codes are still present in these 'living-fossil'' fishes, which offer us the opportunity to trace back the root of these genes," concludes Guojie Zhang.

For more prehistoric type news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.