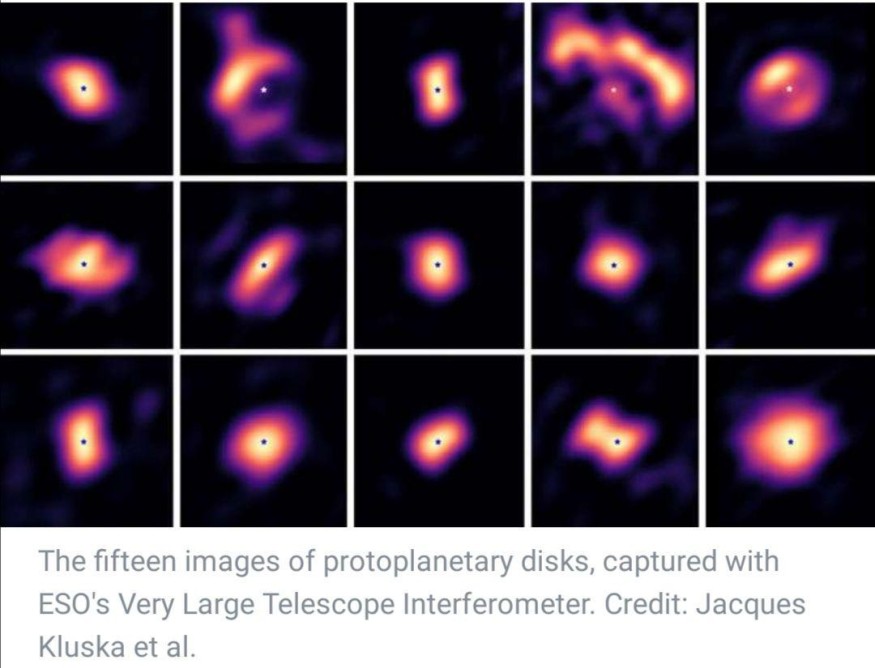

A paper has been published in the Astronomy & Astrophysics journal featuring insights on how planetary systems and planets form. Astronomers have been able to photograph 15 images showing planet-forming disks and their inner rims. The disks are hundreds of light years from the Earth.

The study is entitled: "A family portrait of disk inner rims around Herbig Ae/Be stars: Hunting for warps, rings, self-shadowing and misalignments in the inner astronomical units."

Planet-forming disks are composed of gas and dust and are shaped similarly like vinyl music records. They form around stars that are still young. Understanding the formation of planetary systems requires the studying their origins.

Planet-forming disks are technically known as protoplanetary disks. They form together with the star that they are orbiting. The disks' dust grains can accumulate and become larger bodies, eventually becoming planets. Scientists think that rocky planets like Earth form from the inner parts of these protoplanetary disks while they are five times nearer to its star than the Earth's current distance from the sun.

The new study was groundbreaking because it produced the clearest images that have ever been produced of these disks. Jacques Kluska from Belgium's KU Leuven and the study's lead author said that before, they were only photographed using the biggest single-mirror telescopes, which only produce a few pixels worth of images.

Kluska said that finer details are needed to identify the patterns that will reveal how the disks form into planets as well as characterize their properties. To do this, a another observation technique need to be used, and this technique is infrared interferometry.

The 15 protoplanetary disk images were taken using the new technique at the ESO or European Southern Observatory located in Chile. The study team produced them using the Very Large Telescope Interferometer of ESO.

The detailed images are recovered using mathematical reconstruction. This technique was similarly used in photographing the first ever black hole image. To produce a clearer picture, Kluska and his team also eliminated the star's light which prevented them from capturing the disks' needed details.

The way the astronomers distinguished the details is comparable to looking at a detailed human image at the Moon, or clearly seeing a strand of hair 10 kilometers away. Université Grenoble-Alpes' Jean-Philippe Berger is a principal investigator of the study who took charge of the work at ESO's PIONIER instrument. He said that infrared interferometry is now being used regularly to collect the minutest details of celestial bodies; combined with advanced mathematics, the observations can be converted to images.

The study authors observed that some spots are more or less brighter, which suggest planet forming processes. For instance, instabilities in the disk can form vortices that allow them to accumulate space dust, letting them evolve and grow into planets.

The team is planning to do more research to identify the irregularities they observed, and Kluska will make new observations that will increase the detail even more and help them witness the planet forming process directly within the disks. Kluska is also currently leading a team that has started studying 11 disks orbiting older stars.

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.