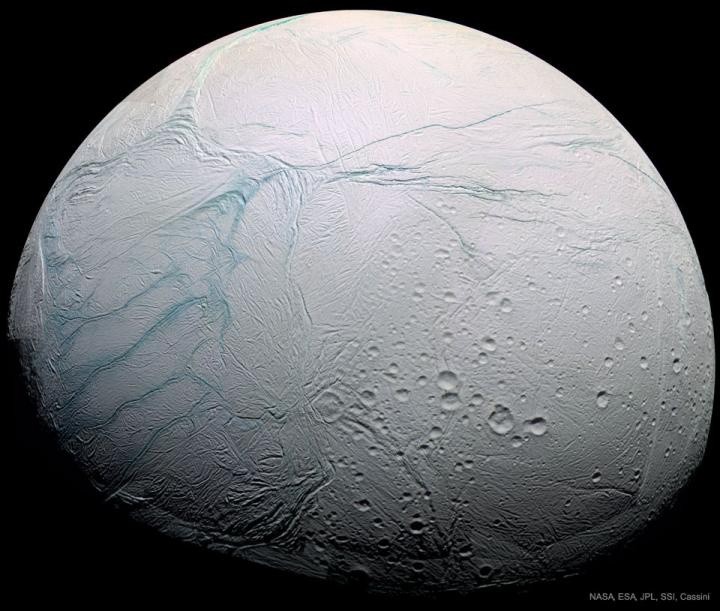

Washington, DC-- Saturn's icy moon Enceladus is of great interest to scientists due to its subsurface ocean, making it a prime target for those searching for life elsewhere. New research led by Carnegie's Doug Hemingway reveals the physics governing the fissures through which oceanwater erupts from the moon's icy surface, giving its south pole an unusual "tiger stripe" appearance.

"First seen by the Cassini mission to Saturn, these stripes are like nothing else known in our Solar System," lead author Hemingway explained. "They are parallel and evenly spaced, about 130 kilometers long and 35 kilometers apart. What makes them especially interesting is that they are continually erupting with water ice, even as we speak. No other icy planets or moons have anything quite like them."

Working with Max Rudolph of the University of California, Davis and Michael Manga of UC Berkeley, Hemingway used models to investigate the physical forces acting on Enceladus that allow the tiger stripe fissures to form and remain in place. Their findings are published by Nature Astronomy.

The team was particularly interested in understanding why the stripes are present only on the moon's south pole but were also keen to figure out why the cracks are so evenly spaced.

The answer to the first question turns out to be a bit of a coin toss. The researchers revealed that the fissures that make up Enceladus' tiger stripes could have formed on either pole, the south just happened to split open first.

Enceladus experiences internal heating due to the eccentricity of its orbit. It is sometimes a little closer to Saturn and sometimes a littler farther, which causes the moon to be slightly deformed--stretched and relaxed--as it responds to the giant planet's gravity. It is this process that keeps the moon from freezing completely solid.

Key to the formation of the fissures is the fact that the moon's poles experience the greatest effects of this gravitationally induced deformation, so the ice sheet is thinnest over them. During periods of gradual cooling on Enceladus, some of the moon's subsurface ocean will freeze. Because water expands as it freezes, as the icy crust thickens from below, the pressure in the underlying ocean increases until the ice shell eventually splits open, creating a fissure. Because of their comparatively thin ice, the poles are the most susceptible to cracks.

The researchers believe the fissure named after the city of Baghdad was the first to form. (The stripes are named after places referred to in the stories of One Thousand and One Nights, which are also called Arabian Nights.) However, it didn't just freeze back up again. It stayed open, allowing ocean water to spew from its crevasse that, in turn, caused three more parallel cracks to form.

"Our model explains the regular spacing of the cracks," Rudolph said.

The additional splits formed from the weight of ice and snow building up along the edges of the Baghdad fissure as jets of water from the subsurface ocean froze and fell back down. This weight added a new form of pressure on the ice sheet.

"That caused the ice sheet to flex just enough to set off a parallel crack about 35 kilometers away," Rudolph added.

That the fissures stay open and erupting is also due to the tidal effects of Saturn's gravity. The moon's deformation acts to keep the wound from healing--repeatedly widening and narrowing the cracks and flushing water in and out of them--preventing the ice from closing up again.

For a larger moon, its own gravity would be stronger and prevent the additional fractures from opening all the way. So, these stripes could only have formed on Enceladus.

"Since it is thanks to these fissures that we have been able to sample and study Enceladus' subsurface ocean, which is beloved by astrobiologists, we thought it was important to understand the forces that formed and sustained them," Hemingway said. "Our modeling of the physical effects experienced by the moon's icy shell points to a potentially unique sequence of events and processes that could allow for these distinctive stripes to exist."

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.