- Study is the first to include 3D chemistry to understand how a star's radiation heats or cools a rocky planet's atmosphere

- Information will help astronomers know where to search for life elsewhere

- Researchers find that only planets orbiting active stars lose water to vaporization

- Some planets, previously believed to be habitable, receive too much UV radiation to sustain life

EVANSTON, Ill. -- In order to search for life in outer space, astronomers first need to know where to look. A new Northwestern University study will help astronomers narrow down the search.

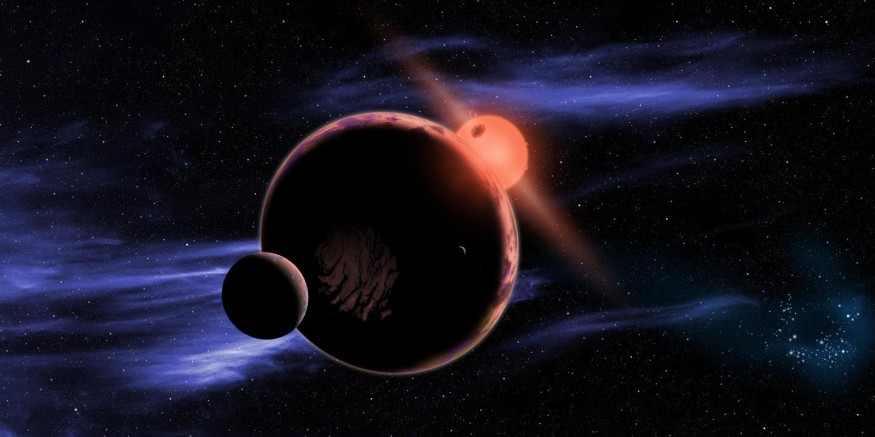

The research team is the first to combine 3D climate modeling with atmospheric chemistry to explore the habitability of planets around M dwarf stars, which comprise about 70% of the total galactic population. Using this tool, the researchers have redefined the conditions that make a planet habitable by taking the star's radiation and the planet's rotation rate into account.

Among its findings, the Northwestern team, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder, NASA's Virtual Planet Laboratory and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discovered that only planets orbiting active stars -- those that emit a lot of ultraviolet (UV) radiation -- lose significant water to vaporization. Planets around inactive, or quiet, stars are more likely to maintain life-sustaining liquid water.

The researchers also found that planets with thin ozone layers, which have otherwise habitable surface temperatures, receive dangerous levels of UV dosages, making them hazardous for complex surface life.

"For most of human history, the question of whether or not life exists elsewhere has belonged only within the philosophical realm," said Northwestern's Howard Chen, the study's first author. "It's only in recent years that we have had the modeling tools and observational technology to address this question."

"Still, there are a lot of stars and planets out there, which means there are a lot of targets," added Daniel Horton, senior author of the study. "Our study can help limit the number of places we have to point our telescopes."

The research will be published online Nov. 14 in the Astrophysical Journal. (Read a pre-print of the paper.)

Horton is an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences in Northwestern's Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. Chen is a Ph.D. candidate in Northwestern's Climate Change Research Group and a NASA future investigator.

The 'Goldilocks zone'

To sustain complex life, planets need to be able to maintain liquid water. If a planet is too close to its star, then water will vaporize completely. If a planet is too far from its star, then water will freeze, and the greenhouse effect will be unable to keep the surface warm enough for life. This Goldilocks area is called the "circumstellar habitable zone," a term coined by Professor James Kasting of Penn State University.

Researchers have been working to figure out how close is too close -- and how far is too far -- for a planet to sustain liquid water. In other words, they are looking for the habitable zone's "inner edge."

"The inner edge of our solar system is between Venus and Earth," Chen explained. "Venus is not habitable; Earth is."

Horton and Chen are looking beyond our solar system to pinpoint the habitable zones within M dwarf stellar systems. Because they are numerous and easier to find and investigate, M dwarf planets have emerged as frontrunners in the search for habitable planets. They get their name from the small, cool, dim stars around which they orbit, called M dwarfs or "red dwarfs".

Crucial chemistry

Other researchers have characterized the atmospheres of M dwarf planets by using both 1D and 3D global climate models. These models also are used on Earth to better understand climate and climate change. Previous 3D studies of rocky exoplanets, however, have missed something important: chemistry.

By coupling 3D climate modeling with photochemistry and atmospheric chemistry, Horton and Chen constructed a more complete picture of how a star's UV radiation interacts with gases, including water vapor and ozone, in the planet's atmosphere.

In their simulations, Horton and Chen found that a star's radiation plays a deciding factor in whether or not a planet is habitable. Specifically, they discovered that planets orbiting active stars are vulnerable to losing significant amounts of water due to vaporization. This stands in stark contrast to previous research using climate models without active photochemistry.

The team also found that many planets in the circumstellar habitable zone could not sustain life due to their thin ozone layers. Despite having otherwise habitable surface temperatures, these planets' ozone layers allow too much UV radiation to pass through and penetrate to the ground. The level of radiation would be hazardous for surface life.

"3D photochemistry plays a huge role because it provides heating or cooling, which can affect the thermodynamics and perhaps the atmospheric composition of a planetary system," Chen said. "These kinds of models have not really been used at all in the exoplanet literature studying rocky planets because they are so computationally expensive. Other photochemical models studying much larger planets, such as gas giants and hot Jupiters, already show that one cannot neglect chemistry when investigating climate."

"It has also been difficult to adapt these models because they were originally designed for Earth-based conditions," Horton said. "To modify the boundary conditions and still have the models run successfully has been challenging."

'Are we alone?'

Horton and Chen believe this information will help observational astronomers in the hunt for life elsewhere. Instruments, such as the Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope, have the capability to detect water vapor and ozone on exoplanets. They just need to know where to look.

"'Are we alone?' is one of the biggest unanswered questions," Chen said. "If we can predict which planets are most likely to host life, then we might get that much closer to answering it within our lifetimes."

© 2025 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.