El Niño is a climatic phenomenon that fluctuates so much over time that scientists will have a hard time discovering signals that it is becoming stronger due to global warming.

Studying 9000 Years of Data

That results from research covering 9000 years undertaken by experts at The University of Texas in Austin. The researchers drew on climatic data found in ancient corals and conducted their research on one of the world's most powerful supercomputers.

The research, which was just published in Science Advances, was driven by a desire to learn more about how climate change could influence El Niño in the future.

The National Science Foundation supported the study, which included a large portion of Lawman's Ph.D. degree. Rice University and the University of Arizona were among the project's collaborators.

Also Read: Gloom Reality: Even the Most Daring Technologies Can No Longer Reverse Impacts of Climate Change

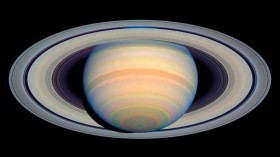

El Niño

El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, a climatic phenomenon that affects weather patterns throughout the world every few years. Strong El Niño episodes, like those in 1997 and 2015, which triggered wildfires in Asia's Borneo rainforests and severe bleaching of the world's coral reefs, occurred around once every ten years.

However, computer models disagree on whether El Niño episodes would get weaker or greater as the world heats due to climate change.

The study's lead author is Allison Lawman, who began the research as a Ph.D. project at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Lawman said that what happens in the tropical Pacific Ocean where El Niño begins influences much of the world's temperature and rainfall. For infrastructure and resource planners, the difference in rainfall between more or fewer strong El Niño events will be a critical question.

Utilizing Complex Sources

Lawman and her colleagues utilized the Texas Advanced Computing Center's Lonestar5 supercomputer to perform a series of climate simulations of an era in Earth's history before human involvement when the primary driver of climate change was a tilt in the planet's orbit. Lawman used a coral emulator he had previously constructed to compare the simulations to climatic records from ancient corals.

They discovered that, while the frequency of intense El Niño episodes increased with time, the increase was minor compared to El Niño's very unpredictable character.

According to study co-author Jud Partin, a research scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, it's like attempting to listen to gentle music next to a jackhammer.

To do so, Partin, Lawman, and the other authors of the paper advocate for greater research into even earlier periods of Earth's history, such as the last ice age, to examine how El Niño responded to more dramatic climatic shifts.

According to co-author Pedro DiNezio, an associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, scientists need to keep pushing the limitations of models and look at geological intervals deeper in time that might indicate how vulnerable El Niño is to climate change. Because if another huge El Niño occurs, it will be difficult to trace it to either a warming climate or El Niño's internal changes.

Related Article: How Climate Misinformation Through Social Media Worsens the Battle Against Climate Change

For more news about similar news, don't forget to follow Nature World News!

© 2024 NatureWorldNews.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.